Autumn light, soft warm and perfect for the colours of the dying trees.

This time of year has to be one of my favourite for colour photography. Early morning mist and dew covers the leaves, flowers and cobwebs perfect subjects for close focus and macro work.(Kodachromes in the mail)

The longer more dramatic shadows and the yellow light make great subjects also.

One of the best photographic lessons anyone ever taught me, was when a friend of my father gave me a roll of Ektachrome 64.

He had one proviso: 'use this roll of film to take a picture of your favourite scene every day for the next month.'

I thought he was crazy, won't it get boring? who would want to see 30 shots of the same thing?

The month was October, my chosen scene was a local ruined church almost obscured by trees, I had to shoot it when I could, and this often worked out at different times of the day.

He processed the transparencies for me and put them into clear sleeves, he then showed them to me on his portable light-box.

I was actually pretty surprised, when I surveyed the film in front of me, every single image was different. Different colours, saturation, some were yellow a couple looked blue/cyan.

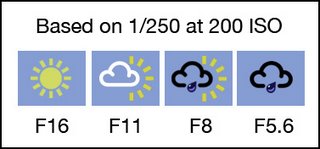

But the lesson it taught me as we never just photograph a subject, but rather the light falling on that subject and here in the UK the light often changes by the hour:- so if you see an interesting scene photograph it.

After all it may be a unique moment in time.